Why vaccines work: an interview with Tracy Yuen

World Immunisation Week aims to promote the use of vaccines to protect people of all ages against disease. This year’s theme is #VaccinesWork, so we sat down with ChildFund Health Advisor Tracy Yuen, to talk about her work to ensure children around the globe have access to what is widely recognised as one of the world’s most successful and cost-effective health interventions.

1. The hopes of the world are now resting on the development of a COVID-19 vaccine. Can you tell us why vaccines are so important in saving lives?

Vaccines are one of the greatest inventions of medicine and public health. They have saved millions of lives of children around the world, in rich countries and poor, while also preventing illness, and lifelong, disease-associated disability.

Unlike medicines that are used to treat disease, vaccines strengthen our immune systems and prevent individuals from falling ill in the first place. This saves money in medical systems and treatment programs and reduces the financial burden on parents who would otherwise need to seek proper healthcare if their child were to contract a disease.

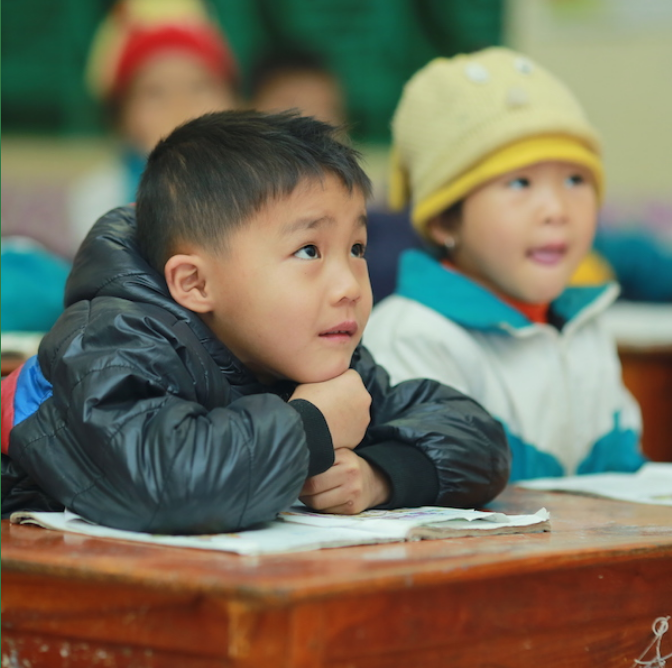

In the communities where ChildFund works, this is really important. Parents are often unable to afford the costs of education or nutritious food, let alone use their savings and take time from work to care for a sick child.

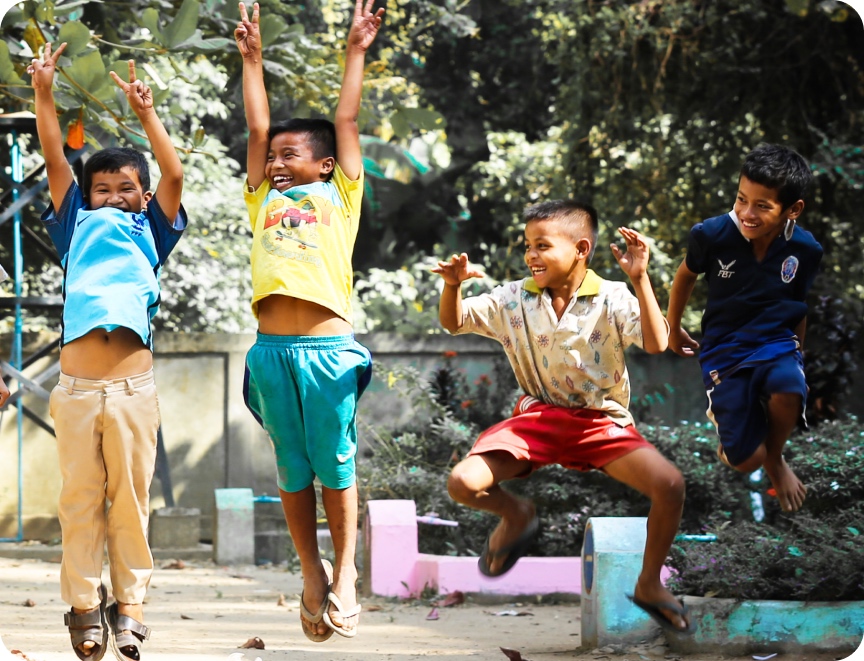

For children, being safe from the myriad of childhood diseases present in the world means their lives are protected, they aren’t missing school due to illness, and they can focus their energies on breaking the cycle of disadvantage and building a better future.

2. ChildFund works with many remote and rural communities in the Asia-Pacific region. What challenges do children and families face in accessing vaccination programs? How do you overcome these obstacles?

In many of the countries where ChildFund works, parents will walk for a whole day to get to a health facility to vaccinate their child. They know how precious this gift of immunity is.

Unfortunately, they can face many barriers in order to protect their children from preventable disease.

In Papua New Guinea (PNG), the health system is so under resourced that mothers will often walk all the way to the nearest health post, only to find a facility struggling with a shortage of both staff and treatment options.

Drug shortages are common in remote and rural areas. As many vaccines come in vials with 10 doses, a healthcare worker in a small, under-resourced facility can be forced to make some difficult decisions. For example, if there are fewer than 10 children in attendance, the health worker may ask parents to return at another time to maximise the doses available and ensure none go to waste.

In theory, there should be sufficient stock in all clinics but, in reality, these workers live with constant drug shortages and must make a call on how to best use their very limited resources for their population in need.

Unfortunately, these shortages can erode trust in the health system and prevent mothers from returning if they feel their time will be wasted. If parents need to pay for transport to and from the clinic, the chances of a repeat visit are even less likely.

In villages located remotely in the mountains, parents often rely on government-led outreach vaccination campaigns. But these too can be unreliable – due to funding shortfalls, a broken vehicle at the health centre, or when vaccine stocks haven’t been replenished.

ChildFund plays an important role in helping parents in rural communities to access healthcare. Our teams work in partnership with district health departments to fill the gaps. This could involve providing portable vaccine coolers and cold chain equipment, or transporting health workers in our cars.

We have also established strong and effective health volunteer networks, which means we can advise communities that an outreach day is coming. With poor mobile coverage in many communities, volunteers usually walk from one household to another. In Laos and Vietnam, this is not always an easy feat as in some villages, houses are situated hills apart; you may not hear from your neighbour for days.

But this communication is incredibly effective and means as many parents as possible know to bring their children to a central village for the day.

3. Are there any traditional or cultural beliefs that make families reluctant to get their children immunised? How do you reassure communities?

I don’t think I’ve come across any traditional beliefs which discourage parents from vaccinating their children, although there are plenty surrounding childbirth. Instead, there are localised rumours that can pop up in response to certain events.

I recall one case where mothers became worried after some children came down with diarrhoea following a vaccination campaign. This had not occurred in any surrounding villages where the vaccine had been administered, so it was more likely that there was a stomach bug going around at the same time.

However, word of mouth can be very powerful, and this became a common concern for that community. The only way we can combat such rumours is by acknowledging the concern and talking to parents and community leaders on why it doesn’t make sense, and instead promoting the benefits of vaccines.

I also recently read about a tragic story during the Samoa measles outbreak. Some parents were reluctant to vaccinate their children because of an earlier event where two babies had died. This wasn’t a reaction against the vaccine; instead the nurses had acted in negligence and mixed the doses with an anaesthetic instead of the correct solution.

But it created a widespread fear that lowered vaccination rates in the country dramatically and led to the outbreak of more than 5,700 cases and over 80 deaths. For a country with a population of around 200,000, these numbers were significant.

4. In recent years, we have seen the re-emergence of polio in PNG, and a measles outbreak in Samoa. What were the causes of these outbreaks?

The reappearance of polio in PNG was a real wake-up call. Vaccination rates and other health indicators had been falling for some time and it really was a ticking bomb waiting to happen.

The lack of investment in PNG’s health system has left large areas of people under-vaccinated, and unfortunately this resulted in what is known as “vaccine derived poliovirus”.

Essentially, there are two forms of the polio vaccine: a ‘live’, orally administered version that is cheap and easy to deliver, and an inactivated “dead” vaccine, delivered through an injection.

The ‘live’ vaccine used in PNG uses a weakened version of the poliovirus that can’t make you sick but provides enough exposure for you to develop immunity. This vaccine gets delivered as a couple of drops in the mouth, makes its way through the body and is then passed out in your stool. Use of this vaccine in the past had led to PNG being declared polio free in 2000.

Unfortunately – and only rarely and in situations where a population is severely under-immunised – the virus can be picked up, spread, and over several generations of passing through unvaccinated individuals, has the potential to mutate back into a virulent form that can paralyse. This is what happened in PNG.

In Australia, we use the inactivated vaccine. It is more expensive and requires a health worker to give you an injection, but doesn’t have this issue.

But because low income countries have poor health systems and can’t afford to mass vaccinate their populations with the inactivated polio vaccine, they are still using the oral one. It is generally very safe and has helped eliminate polio from countless countries, but it still contains a very rare risk that resulted in the emergence of polio in PNG.

5. We are seeing reduced vaccination rates in developed countries, including Australia. How can we encourage more families to vaccinate their children?

The rates of vaccination in Australia are actually really good, at around 95%. It is only in small, specific communities that we are seeing low rates of immunisation. Unfortunately, those pockets create areas of vulnerability and are where you will see sporadic outbreaks of diseases such as whooping cough, which can be life-threatening particularly among newborns.

It can be very hard to change the minds of people who don’t agree with vaccines, so the best thing we can do is to promote overall science literacy and critical thinking among all Australians, both at school and as adults.

We need to encourage people to ask questions and think about what goes into their bodies, but we also need science and health educators to explain how vaccines work, how incredibly effective they are at preventing dangerous diseases, and what little risk they pose in comparison to some of the everyday products and medicines that people routinely take.

Thanks to our high rates of vaccination in Australia, our kids are doubly protected, once through the individual immunity of receiving a shot, as well as protection offered by ‘herd immunity’. This means that because the majority of people around you are immune, you are less likely to encounter a disease. Herd immunity also ensures that individuals who cannot be immunised for medical reasons are kept safe from infection by those who have.

In many of the communities where ChildFund works, there is no herd immunity. Sadly, parents continue to lose their children to preventable disease, and outbreaks can grow rapidly.

But we know that improvements in child health outcomes are possible in all regions of the world. Australia is a great example of how the combination of widespread vaccination campaigns, accessible health information for parents, and a strong health system can relegate many feared childhood diseases – such as polio – to history.

Donate now, and help protect vulnerable communities from COVID-19

ChildFund has adapted our development programs to face the threat of COVID-19 in communities across Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea and Cambodia, but we need your help.

Donate to our COVID-19 crisis appeal today and help stop the spread among vulnerable communities.

About Tracy Yuen

Tracy is the Health Advisor at ChildFund Australia. Having worked previously in biomedical research, Tracy was involved in the design of vaccines for infectious diseases. She transitioned to public health in 2012, and in her role at ChildFund now provides technical and strategic support to programs covering maternal and child health, nutrition, and water and sanitation across the Asia-Pacific region.