Sixteen-year-old Diep lives in a village in northern Vietnam. When she began school more than a decade ago, teachers relied on textbooks for sharing knowledge.

There were no computers in the classroom or ways to access the internet. Living in an isolated rural area, children like Diep rarely had the opportunity to travel to other areas of the country, let alone the opportunity to connect with the world outside Vietnam.

Ten years later, and life for Diep and other young people in her neighbourhood is very different, with ChildFund Vietnam now implementing a range of child-focused initiatives in her community.

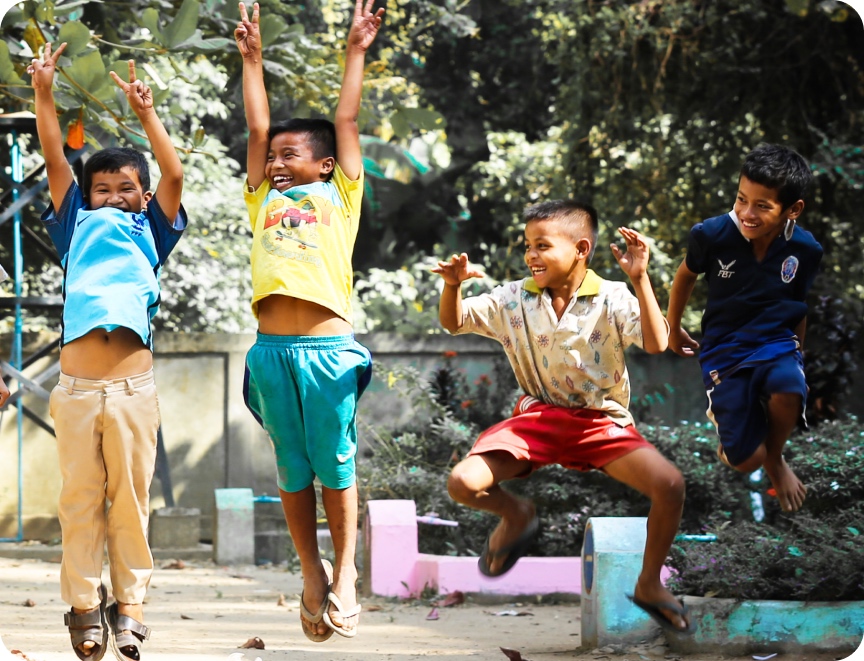

ChildFund’s projects focus on child rights and child protection, education, health, and wellbeing for children. ChildFund Vietnam also prioritises building the resilience of young people, by giving them the opportunity to take part in sports, life skills learning, and supporting their participation in local decision-making processes.

Today, not only has Diep been given the opportunity to take part in organised sport for the first time, she has a new role as a Pass It Back rugby coach and can be found blowing her referee’s whistle while her all-girl team practise their skills on a local field.

When disasters strike, Australians have demonstrated time and time again that they are happy to lend their support to humanitarian aid efforts around the globe. We spoke to ChildFund Australia’s Emergency Response Advisor Michael McDonald to find out more about how humanitarian aid works in practice, and its benefit for children and families living through crisis.

What is humanitarian aid?

This is a form of assistance that is used to respond to disasters that can be natural, biological (as with COVID-19) or conflict related.

Generally, it is provided over a short period ranging from 3 to 12 months, and funds the provision of shelter, food, household items, health services, and water sanitation and hygiene.

Humanitarian aid is different to development aid as the latter is provided on a longer-term basis, and builds government and civil society systems in areas such as health, education, and child protection.

Development aid is focused on achieving sustained improvements, rather than meeting the needs of an affected population in the short-term.

What types of organisations typically provide humanitarian aid?

Governments, different agencies within the United Nations, international non-government organisations (NGOs) such as ChildFund Australia, local NGOs in the affected country, and private businesses provide humanitarian aid.

It is important to note that governments are the most legitimate actor among those mentioned and so, ideally, all actors should be working in coordination with government according to agreed disaster response plans.

When a disaster strikes, how is humanitarian aid coordinated?

Governments will often have a National Disaster Management Office that has the role of coordinating a disaster response plan. This plan will be based on an analysis of the situation and include feedback from other government departments and often the Red Cross.

The government will often consult with the different agencies of the United Nations, as well as local NGOs, to ensure that the disaster response plan is both comprehensive and representative.

When the number of affected people, and loss of life or injury is high, governments can easily be overwhelmed.

If so, they may request international assistance. The United Nations will coordinate the many international organisations that arrive to assist with the response.

This system sits parallel to the government system and will comprise of working groups which focused on areas such as:

- food security,

- nutrition,

- health,

- education,

- shelter,

- non-food items.

Each of these working groups will be co-chaired by a United Nations representative and, ideally, by a government representative to ensure a link to the government response is maintained.

Is humanitarian aid only provided to developing countries, or do countries like Australia also benefit from international assistance when disasters strike?

All countries are sovereign, meaning that their governments can either accept or reject any humanitarian aid that is offered.

Australia is no different. When a disaster strikes in Australia, the Australian government can decide whether to request international assistance or not.

If it decides to do so (most likely because it is overwhelmed), then humanitarian aid will arrive in Australia.

A good example of this is the US water bombing aircraft that were provided during the Bushfire Disaster in 2020-21. This assistance would have been requested by the Australian government as our own resources were being pushed to the limit at that time.

This goes to show that both wealthy and less wealthy countries will at times request humanitarian assistance.

Is it possible to measure the impact of humanitarian aid?

As with many sectors, the humanitarian aid sector has indicators of success. These indicators have been developed through extensive consultation with actors from within the sector and are updated periodically.

A well-known universal indicator among those who work on water, sanitation and hygiene in disasters is that every member of the affected population should have access to 15 litres of water per day for drinking and domestic hygiene.

What do you think are some of the most pressing humanitarian aid issues of the 21st century?

In big disasters, such as that unfolding in Myanmar now, the United Nations together with other UN member governments will develop a humanitarian response plan.

We are seeing a significant increase in the number of large disasters occurring around the globe. This includes the displacement of Myanmar’s Rohingya people; war and conflict in Syria, Yemen, and South Sudan; and more recently, escalating ethnic tensions in Ethiopia’s Tigray region. Unfortunately, many of these humanitarian response plans lack funding, with obvious consequences for the affected population.

As per international law, when someone is being persecuted in their own country, they have a right to claim asylum in another country. Unfortunately, given the number of people claiming asylum today and the hardening of politics within many countries, asylum seekers are not being allowed to pass through due process to access their legitimate rights to asylum.

This recognition would allow them to access the services they need to live a dignified life in a country in which they feel safe and secure. Rather, these people are being pushed from one country to the next.

In areas such as the Pacific Rim, climate change is exacerbating the frequency and severity of natural disasters.

ChildFund Australia works in Fiji where, over the last 12 months, the country has been hit by COVID-19 as well as five moderate to severe tropical cyclones.

These disasters cause significant community disruption, great material loss, injury, and loss of life. They also have the potential to cause economic hardship, given the cost of the disaster response. It can also put at risk many of the hard-won development advances in recent decades.

About Michael McDonald

Michael McDonald is ChildFund Australia’s Disaster Risk Reduction/Emergency Response Advisor and is based in Sydney. Prior to joining the organisation in 2018, Michael held a range of humanitarian response positions internationally. As an example, he worked on the Syria Crisis in Jordan with asylum seekers from Syria and from Jordan cross-border into Syria with the affected population in southern Syria. Currently, Michael works in close partnership with ChildFund Australia’s country offices in the Asia-Pacific region to reduce the vulnerability of children and their families so as, when natural disasters strike, they are less likely to be severely impacted. Michael also supports any disaster response efforts in the region when natural disasters do occur.