The forgotten right: children’s right to play

Thirty years ago, governments around the world adopted the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).

This was a watershed moment – for the first time, children and youth under the age of 18 were recognised as having distinct and particular human rights relating to their survival, development, protection and participation.

The CRC has since become the most widely ratified human rights treaty and has driven a huge amount of progress for children.

Articles within the CRC have informed Australia’s national targets and action plans, and have also underpinned goals in the global development agendas –such as the Millennium Development Goals and the current Sustainable Development Goals.

Enormous progress has been made in the past thirty years on children’s survival rates, access to education, poverty reduction, improved nutrition, access to healthcare and commitments to protect children from violence.

While this progress should be celebrated, it is evident that in many regions of the world children’s rights continue to be ignored and violated.

One of the rights frequently overlooked in the CRC is Article 31, children’s right to relax and play, and to join in a wide range of cultural, artistic and other recreational activities.

Despite play being a defining feature of childhood and holding extraordinary benefits for children, it is often ignored and undervalued. Instead, the ‘serious’ rights, such as the right to health, education and protection, receive greater attention.

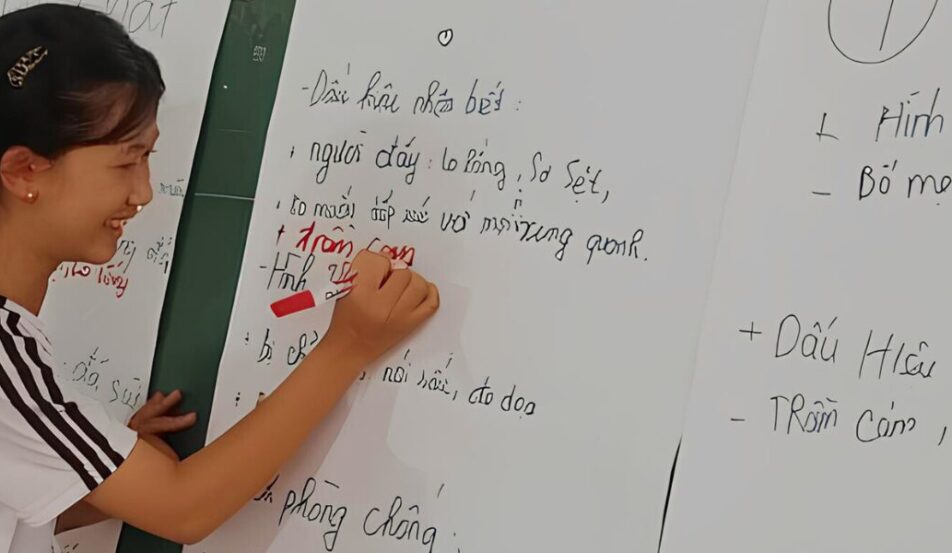

Research on the benefits of play in all its forms – informal and structured, physical and creative – is conclusive. Play develops creativity and imagination, enhances physical and emotional health, contributes to healthy brain development, and is essential to the development of social and emotional ties.

Play enables children to explore and understand their world, and fosters the development of social skills such as teamwork, conflict resolution, leadership and problem-solving. The American Academy of Pediatrics says that ‘play is so central to child development that it should be included in the very definition of childhood’.

Play is central to children’s lives and the research points to its many benefits. However official data on this right is negligible and it is rarely the focus of national or international agendas. Unlike health or education which are routinely measured by governments and UN agencies, there is no global data available on children’s access to play.

The assumption appears to be that it is either not important enough to warrant official attention or that play occurs naturally and spontaneously for children, so there is no need to adopt rigorous systems to measure its prevalence.

However, in Australia and around the world, children’s right to play is under threat.

For children in poorer communities, free time can be limited. Children use their time outside of school hours to collect water, undertake domestic chores, help with household income-generation activities or care for younger siblings while parents are at work. In some of Australia’s neighbouring countries, one in five children work; they do not attend school and have little time to play.

With increased urbanisation and a lack of planning for recreational infrastructure, the availability of safe, accessible outdoor spaces is becoming limited – particularly in the world’s megacities, which proliferate in our region. For girls, high levels of harassment, crime and violence act to discourage their involvement in play and recreation outside the home.

In Australia, despite our reputation as a nation obsessed with sport, physical activity rates among children are on the decline. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare finds that 80% of children are not meeting physical activity recommendations, and childhood obesity is increasing.

One factor is the ‘over-scheduling’ of children, with children in 2019 undertaking many more extracurricular activities than previous generations. While many of these activities are forms of structured play, the pressured timetables allow little time for informal free playtime.

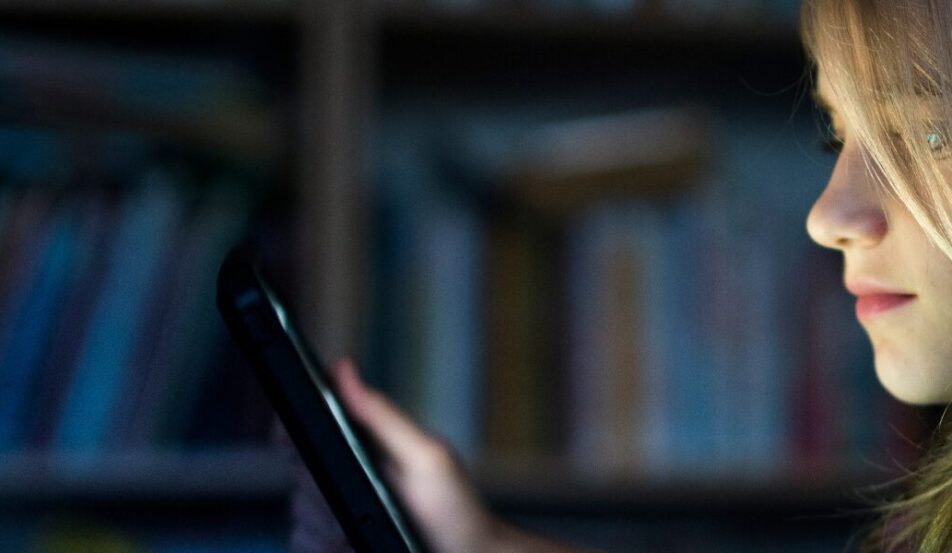

The advent of new technologies is also changing how children play, particularly among adolescents. Online gaming proliferates and reduces the time available for physical or creative recreation. The worldwide web brings extraordinary new opportunities for young people to learn and connect. It is now an integral new play domain for children and young people but it also brings new threats to their welfare.

The right to play is included in the CRC because it is essential for children’s wellbeing. But it suffers from neglect. Much greater attention should be given to understanding the opportunities and obstacles to children’s play in Australia and in our region.

Only then can we give play the importance it deserves, and act to ensure that every child has the opportunity to experience a childhood where they can learn, grow and develop through play.