With the highly publicised Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, Australians are acutely aware of the risks and long-term damage that is common among children growing up away from their families.

We’ve learned some heartbreaking lessons in Australia, which means that today, our most vulnerable children are very rarely placed in residential care. If they are, it is a last resort measure, and never on a permanent basis.

Unfortunately, the residential care model continues to persist in many developing countries. Many of these centres are unregistered, under-regulated and under-staffed by workers lacking in any formal qualifications. As a result, children are vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse, neglect and sometimes exploitation. These risks are heightened in facilities where volunteers, tourists and visitors are permitted to have direct contact with children.

Residential care facilities also pose a range of psychosocial risks to children. One of the most well-documented issues is that of attachment disorder, where problems emerge when children are unable to sustain a bond with their primary caregivers. Attachment disorders are common among children in residential care where they are separated from their families and frequent staff turnover is the norm.

Well-meaning Australians frequently support residential care programs in developing countries – and at first glance, one can understand this urge to help children without parental care. It is seemingly an appropriate way to make a small difference to the complex and enormous problem of poverty. Many residential care facilities can also provide positive and tangible evidence of the impact they are having on the lives of vulnerable children. But it’s important to look at the problem carefully.

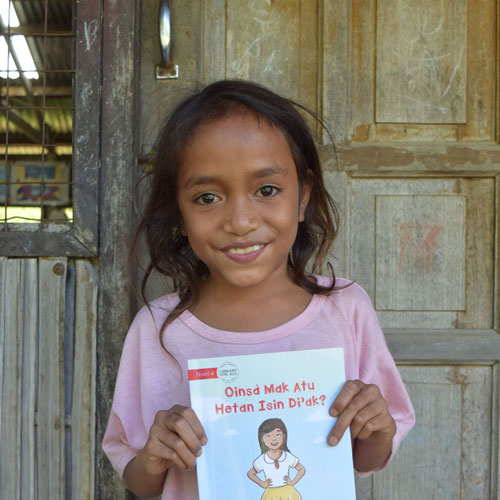

Poverty challenges an individual’s ability to access their basic human rights —for instance, a child’s right to education and healthcare. Children with disabilities, living in poor communities, face even greater barriers.

In developing countries, residential care models are often promoted as an easy solution to the challenges of poverty. For families struggling to survive, it can seem like the only option. It may also appear to be one way in which parents, who generally want the best for their children, can provide the education, shelter and nutrition that they themselves may have missed out on in their own childhoods.

This view is certainly borne out by research findings. In a 2011 Cambodian government study, more than 90 per cent of respondents believed a poor family should send a child to an orphanage for education if they could not pay for it themselves .

In addition, the significant amount of funding enjoyed by residential care centres, usually donated by well-meaning donors, often deprioritises community-development programs. Funding is diverted from those initiatives which help parents to access their children’s rights, and provide the necessary support to ensure children can remain living with their families and local community.

These factors combined means that the availability of residential care is actually incentivising family separation.

ChildFund Australia actively discourages models of residential care that promote the separation of a child from their parents or extended family. Instead, we work in partnership with children, their families and communities to tackle the causes of poverty so that children have greater access to their rights, while remaining among the family and friends that they know and love.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child states: “The family, as the fundamental group of society and the natural environment for the growth and well-being of all its members and particularly children, should be afforded the necessary protection and assistance so that it can fully assume its responsibilities within the community.”

Children have an important and fundamental right to grow up in their families, and it is important that we make every effort to avoid the unnecessary harm caused by separation.